Keeping HHS Safe

There are multiple levels of safety within a school – feeling safe emotionally, feeling safe to make a mistake in class and then learn from that mistake, and, most importantly, feeling physically safe in a learning environment.

Often, the awareness of “feeling safe” isn’t something that is at the forefront of most people’s minds; it’s the awareness of potential danger that can cause stress and be a hindrance to learning. The best barometer of students feeling safe in their school is when the students aren’t thinking about the issue of safety at all; they are simply allowed to be kids and learn to the best of their abilities.

In Haywood County Schools, a School Resource Officer (SRO) is placed on every campus to ensure the physical safety of all students. SRO’s are trained police officers who have graduated from The Tennessee Law Enforcement Academy and have previous experience as a law enforcement officer.

The job of an SRO requires a specialized skill set that sets them apart from police officers who are on patrol within a community. SRO’s must have the ability to build relationships with students, engage with teachers, and, above all, help protect everyone in the school building.

To be successful in any profession, an awareness of nuance is a key ingredient that is often overlooked. Being able to evaluate any given situation in a nuanced and detailed way can open multiple doors to solving problems or resolving an issue.

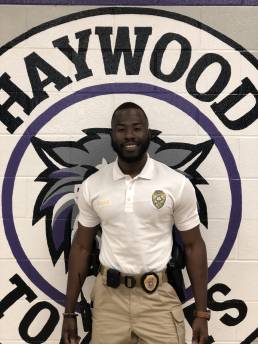

Haywood High School School Resource Officer Isaiah Walker understands the importance of evaluating each situation with patience and depth – skills that are not often seen in an officer his age. Isaiah is only 25 years old and recently completed his first full year as a law enforcement officer in Haywood County.

“August 21 was my one-year anniversary in law enforcement,” he said. “Normally, SRO”s have to have three years of law enforcement experience before being promoted to an SRO, but I was fortunate enough to get this position a little earlier than expected.”

Seven years prior to Isaiah being named the SRO at HHS, he was walking the same halls as a student. Not only does his age allow him to relate to students in an effective way, his experience as an ordained youth minister has also helped him develop skills in building relationships with teenagers which is something that doesn’t always come naturally to adults in positions of authority.

Seven years prior to Isaiah being named the SRO at HHS, he was walking the same halls as a student. Not only does his age allow him to relate to students in an effective way, his experience as an ordained youth minister has also helped him develop skills in building relationships with teenagers which is something that doesn’t always come naturally to adults in positions of authority.

Having experience in building relationships has also helped Isaiah understand how policing within the context of a high school is quite different than policing in the community,

“Policing is a little different inside a building than out in the community. You’re dealing with different age groups, different behaviors, and different thought patterns,” he explained. “In high school, students are very concerned about what their peers think and say and behaviors are often dictated by those things. The plus side to policing in a high school, though, is that there are many opportunities to build relationships with the students. If the students are reprimanded for something, there’s time to talk it out and possibly get to the root cause of the behavior.”

This is where Isaiah’s skillset of seeing the nuances of a given situation help him interact with students and, hopefully, help change students’ behaviors moving forward. He realizes that given behaviors don’t occur in a vacuum; there are often a variety of reasons that students are acting out or violating school policy.

“Sometimes the situation we’re dealing with in the school is a symptom of what’s going outside the school – maybe what’s going on at home or in the community,” he said. “On the street, if you have the facts to enforce the law then that’s what you do and wipe your hands of it and you’re done. In a school setting, though, there’s the chance to really have productive conversations about behavior and choices. At this age, teenagers are products of their environment; they’re in the process of being a sponge and absorbing what’s around them. A lot of the students that walk through these halls will behave in ways that they’re told to behave or that they’ve observed, but my job is to reassure and reaffirm to them that they’re great and smart and loved and valued.”

This is the type of depth from an SRO that could truly change student behavior rather than put a band-aid on it. While there are definite situations and causes for punitive action to take place, punitive actions cannot solely stand alone with the hope of changing behaviors. Negative consequences must also be paired with constructive and direct conversations that still maintain the dignity of the student while at the same time communicating why certain behaviors could be dangerous and/or unhealthy.

“I’ve learned that many youth and young adults don’t care how much you know until they see how much you care,” Officer Walker explained. “This job really takes patience on my part. Teenagers are impulsive, so adults can’t be. I try my hardest to counteract their impulsivity by remaining calm and just listening to them if they’re upset. Having conversations helps children really think through what’s just occurred.”

Another factor that Officer Walker is well aware of is the perception of law enforcement as school aged children grow older. When students are young, negative interactions with authorities are limited – teachers are treated with unquestioned respect; law enforcement officers are given high-fives and hugs. As children age, however, their experiences with authority figures in their lives begins to change in some cases. If students have multiple negative interactions with teachers, they may take a little time to warm-up to a teacher the next year; the trust takes a little longer to rebuild each time. The same can be said for interactions with law enforcement officers.

“By the time students reach high school, they more than likely have a certain view of police based on their personal experience. I realize that that particular experience probably isn’t a positive one; police officers aren’t getting invited to pizza parties or anything like that. When we’re called in the community, it’s usually because something bad has happened,” he said. “This job as an SRO is a calling; I believe that. In this role, there’s a chance for me to change a perception that might be negative. I believe that the only way people’s perceptions change is through consistency and positivity. I’m trying to be both. My door is always open if a student needs to talk because I see myself as more than just a law enforcement officer. Love is given, but respect is earned. If I continue to show them respect, they’ll show me the same.”

While Officer Walker has an excellent grasp of the nuances of policing in a school setting, he is also very aware of the concrete aspects of his job such as building security and the physical protection of students and staff.

“The high school is the largest campus in the district. We’re split into three buildings here, so there are a lot of doors to be checked. I survey all three buildings; I’ll drive around the campus to make sure no doors are visibly accessible. Then, I’ll walk the halls and check bathrooms and also take that time in the morning to just catch up with students about their weekend or their previous night,” he said. “When students are in class, I always want teachers to make sure their doors are locked. I’ll go to the Career/Tech building and check the doors there. I’ll make my rounds four or five times a day.”

Even with the knowledge of navigating student interactions and the skill to provide protection, Officer Walker is also very aware of something that the general population takes for granted: the access to personal, handheld technology by students. And, like almost everything else in his job, Officer Walker sees both sides of it.

“Something that the general population may not think about that’s actually very important to school safety is how much access students have to cell phones. That can actually be good or bad. The use and importance of technology can alert us to something that we may not know but absolutely need to know,” he explained. “On the other hand, that access to technology can also produce issues that we have to follow up on.”

With as much depth and intelligence as Officer Walker brings to the job, he also is well aware that all of that depth and intelligence won’t get him very far if he doesn’t show students that he genuinely cares about their safety and success.

With as much depth and intelligence as Officer Walker brings to the job, he also is well aware that all of that depth and intelligence won’t get him very far if he doesn’t show students that he genuinely cares about their safety and success.

“I’ve been an ordained youth minister since 2017 and have worked with youth and young adults the whole time. I feel like I’ve had a lot of practice at interacting with young people and showing them who they can be – revealing that potential each of them have,” he said. “I plan to do this for a long time, so I want students who leave HHS to know that Officer Walker has their back here and wherever else they go when they leave.”